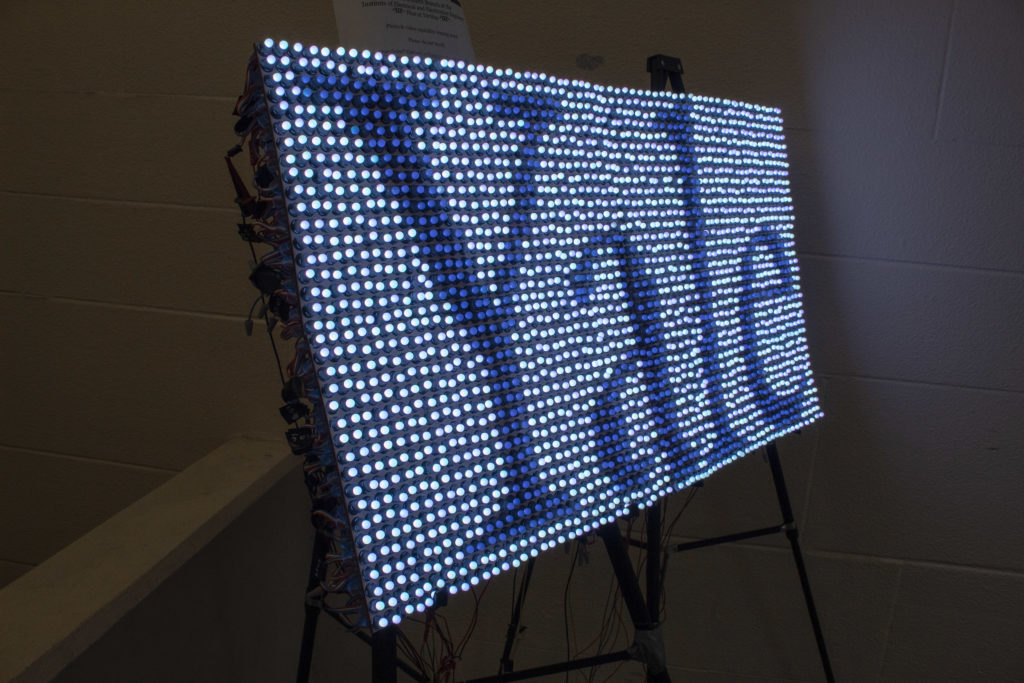

Courtesy of Kai Nip

Researchers from several American universities are collaborating to develop artificial intelligence based software to help people on the autism spectrum find and hold meaningful employment.

The project is a collaboration between experts at Vanderbilt, Yale, Cornell and the Georgia Institute of Technology. It consists of developing multiple pieces of technology, each one aimed at a different aspect of supporting people with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in the workplace, according to Nilanjan Sarkar, professor of engineering at Vanderbilt University and the leader of the project.

“We realized together that there are some support systems for children with autism in this society, but as soon as they become 18 years old and more, there is a support cliff and the social services are not as much,” Sarkar said.

The project began a year ago with preliminary funding from the National Science Foundation. The NSF initially invested in around 40 projects, but only four — including this one — were chosen to be funded for a longer term of two years.

“We’re very excited to be part of that selection,” said Brian Scassellati, the A. Bartlett Giamatti professor of computer science, mechanical engineering and materials science at Yale. “I think it’s a recognition of how important this problem is and how close we are to being able to help people.”

People on the autism spectrum tend to have strong visual reasoning abilities and often see puzzles differently from how a neurotypical person might see them. Companies find it beneficial to hire people with strong visual and spatial abilities because these skills can be very useful, especially for working in technology, according to Maithilee Kunda, assistant professor of computer science and computer engineering at Vanderbilt University.

Kunda leads the effort to develop AI and cognitive modeling that analyzes a person’s visual reasoning abilities. Then, based on the analysis, people are connected with job positions they might excel in. This is done through an assessment consisting of a series of puzzles during which the test-taker wears an eye-tracker and is monitored with cameras. The researchers then use the measurements they take from both the sensors and the test to study the visual thinking process of the test-taker, according to Kunda.

Several years ago, Kunda realized “you can give two people the same set of problems to do and they can both be equally successful solving the problems correctly, but they could be doing it in completely different ways,” she said. “This is like the great mystery of cognitive science. All these things are happening inside your head and we cannot directly measure them.”

Eighty percent of people with ASD are either unemployed or underemployed, according to Sarkar. However, Kunda pointed out that often the issue is not with someone’s job abilities but rather with their social skills.

Sarkar and his lab are creating an interview simulation that would allow someone to practice the interview process, which is often difficult for people with ASD. The interviewing simulator tracks the participant’s stress levels as they undergo a practice interview. Once the sources of an individual’s stresses are known, the individual can work to overcome their stress and better manage their social anxiety.

Sarkar is also working on a “collaborative virtual environment” in which people can practice working in teams. A group of people are given a virtual task and they must work together to accomplish it. There is an artificial intelligence agent embedded in the software which can help participants if they get stuck and also provide advice on how to improve their social interactions.

One of the great challenges of this project is how to measure if people retain the social skills they learned in the virtual setting and can apply them in a face-to-face setting as well.

“People can make gains in very specific settings where they are being trained, but those gains sometimes don’t translate to the actual settings in which they are performing their work or where the actual interview is happening,” said Jim Rehg, a professor in the School of Interactive Computing at the Georgia Institute of Technology. “We want to be able to validate or verify that those gains are being preserved, that they are being exhibited in real life settings.”

Rehg and his team give eye-tracking glasses to both the interviewer and the interviewee to follow the paths of their eyes during the interview. The researchers then use the algorithm they developed to analyze the two videos, taking into account eye contact, posture and gestures to identify irregular patterns.

While interviews and collaborative assignments can cause stress in people with ASD, so can simply being in the workplace and dealing with interruptions to their work, according to Scassellati.

“It doesn’t matter whether you are stocking grocery shelves or whether you are doing data entry or running a high-profile money market, whatever job you’re doing there are going to be interruptions during the day,” Scassellati said. “Minor day-to-day interruptions can be real challenges for adults with ASD in the workplace.”

Scassellati and his team at Yale are tackling this everyday challenge by building a social robot to help neurodiverse people practice coping with interruptions. The social robot is designed to be used in the home, and it is programmed to ask the user questions while they are involved in other activities such as watching TV. The robot pays attention to whether the person addresses the question and uses the appropriate social conventions.

Susanne Bruyere, director of the Yang-Tan Institute on Employment and Disability at Cornell, works with the aforementioned researchers to better understand the barriers faced by people with disabilities in the workforce, so that the technologies being developed can address them more specifically.

“We believe that people with disabilities add a needed element to the richness of the American and global workforce,” Bruyere said.

The project’s technology is still in the beginning stages of development. But two years from now, the team expects to deploy some of their innovations to their partners, including the Vocational Rehabilitation Facilities. The research team has also connected with several large private sector companies such as Ernst & Young, SAP and Auticon which have expressed interest in testing the technology at their firms.

Because the project is mostly software-based and the researchers do not need to wait for new innovations in hardware, Scassellati expressed hope that the products might be available soon.

“This is the kind of thing that could go into production very quickly, so we do have some hope that this is not 30 years off or 10 years off but maybe even just a few years off,” Scassellati said.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 5.4 million adults in the US are on the autism spectrum.

Emilia Oliva | emilia.oliva@yale.edu